The Untold Truth Behind Stephen Kent’s Bold Call to Regulate Sports Betting Now

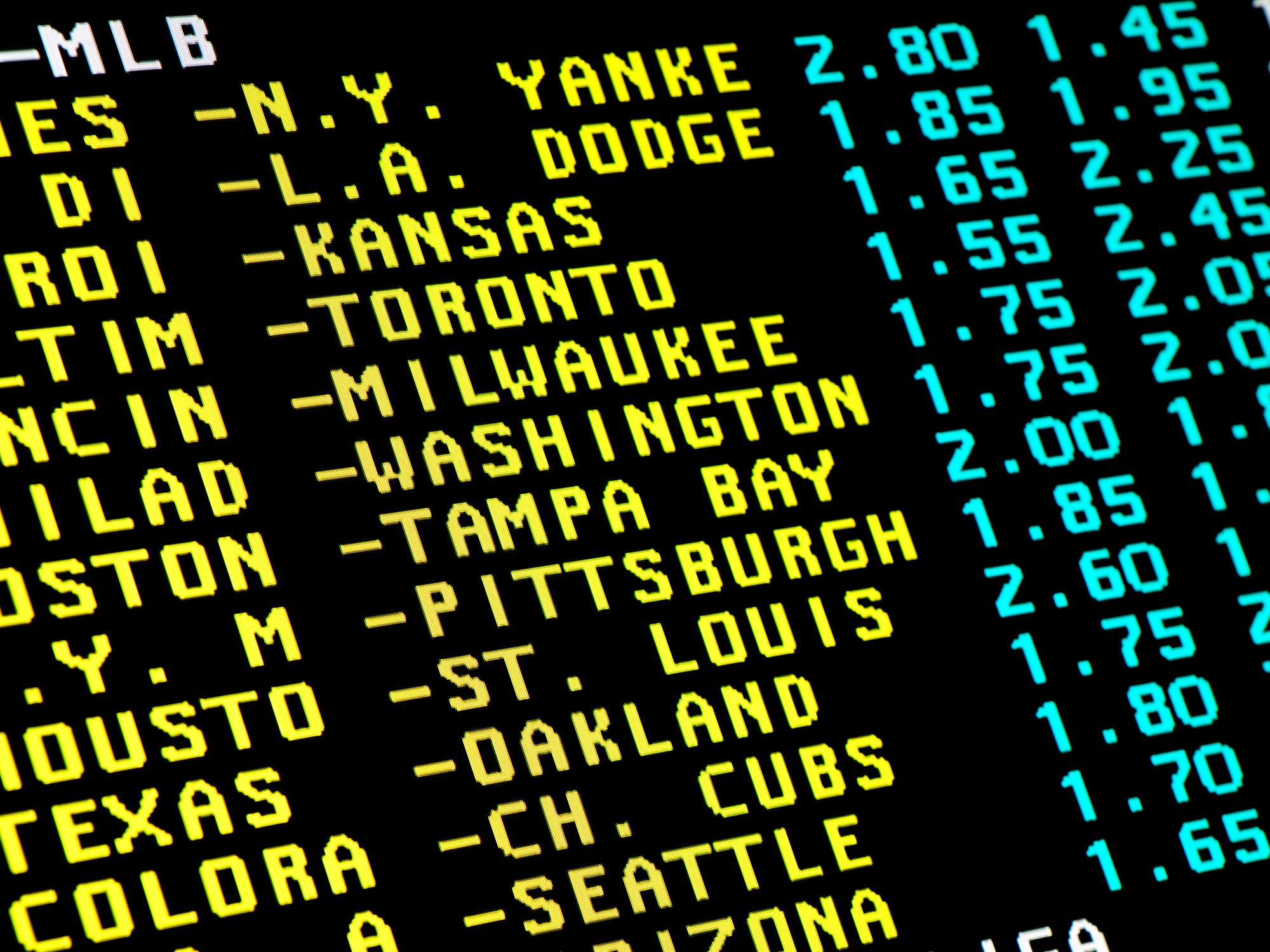

Since the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision to strike down PASPA, sports betting has exploded from a hush-hush pastime to a booming $18 billion industry across 38 states—turning casual wagers into mainstream entertainment. But here’s a question that pokes the bear: Why does Texas, home to the Cowboys, stubbornly keep its doors shut to legal sports betting, pushing fans offshore and to neighboring states? As the NFL season kicks off, the clash between regulated markets and the wild west of offshore bets reignites. And while critics warn about rising gambling woes, the data paints a surprisingly nuanced picture—suggesting that with proper regulation, the game might just be worth the gamble after all. Ready to dive deeper into this complex playbook? LEARN MORE

Since the Supreme Court’s 2018 decision to strike down the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA), sports betting has been legalized in 38 states and counting, and business is booming. In seven years, it’s become a $18 billion industry, one of the most rapid expansions of a legal consumer market in modern U.S. history—transforming sports bets from a water cooler hobby to standard fare American entertainment.

When the NFL’s new season kicks off in full this weekend, the debate around this growing market is sure to resurface. Thursday night saw the Eagles host the Cowboys in a game in which millions in bets were likely placed. Pennsylvania legalized sports betting just before the SCOTUS ruling, and the Texan home of the Cowboys still doesn’t allow it online or in the state’s tribal casinos.

But only one of those two states is able to log receipts, tax revenue, and regulate it appropriately. Texans will flock to neighboring states such as Louisiana and Arkansas, or flood offshore betting sites, dropping dollars on foreign operators who treat consumer protections as a punchline.

While Texas keeps legal sports betting at bay, new forms of playing the odds are entering the market under a different classification, such as prediction market apps like Kalshi. Instead of players betting against the house, like with a sportsbook, these are peer-to-peer contracts where individuals buy and sell futures for different contests.

One doesn’t have to like sports betting or any form of gambling in order to acknowledge that it happens despite its legal status. You also don’t have to believe there are zero harms associated with placing bets to approve structured regulation that mitigates the harms to those on the fringes of society.

Research critical of sports betting has pointed to upticks after legalization, which stands to reason. Scott Baker, in a study for the National Bureau of Economic Research, found that only 7.7% of households are bettors, and on average, deposit only $102 per quarter—that’s just $34 per month. Bettors tend to invest less money in the market and spend even more money per month on food and entertainment associated with games.

This could be said of literally any hobby a person enjoys, and there are far more expensive ones out there.

Claims that legalization leads to runaway debt or bankruptcy spikes are not borne out by the data, which show minimal changes in financial health indicators like credit scores and loan delinquency.

The problem with most research critical of sports betting is that it relies on upticks in certain consumer behavior as evidence of harm without having to compare itself to the status quo. A new study from Seton Hall University underscores this point, saying, “Imagine if research on the end of alcohol prohibition focused only on the increase in expenditure on legal alcohol and increased consumption and associated misbehavior, while ignoring the enormous savings from reduced enforcement expenditure, decline in mob-related violence, and increased safety from regulated products.”

It was understood that drinking would increase, as would the necessity for alcohol rehabilitation, but those are countering other harms that proper regulation mitigated. Interestingly enough, alcohol consumption has still dropped to historic lows in the U.S. without new legal crackdowns or rehashed morality campaigns.

We’re seeing similar kinds of reporting on sports betting, such as with Indiana’s self-banning program, which, according to the IndyStar, showed a “staggering increase of over 3,500%” from 12 participants in 2020 to 451 today. For a state with roughly 5 million adults, that’s 0.009% —hardly staggering.

There was no program before 2020, so the number can only go up, and you want people to use it if they have a problematic relationship with gambling.

Legal markets bring these transactions into the light and provide resources and help for Americans who need it. When betting is legal, consumers have access to measurably more responsible gaming tools, certain legal protections, and data-sharing protocols that can flag suspicious betting patterns, enabling sports leagues and law enforcement to detect and investigate potential match-fixing.

Illegal markets have no such incentives or mechanisms. Only in legal frameworks do we have any sense of whom to blame for problems and who to hold accountable for abusive practices. That’s a key difference.

Arguments about economic benefits associated with sports betting have fallen out of favor on the populist right, captured by figures including Saagar Enjeti and Tucker Carlson, but it remains true that $1.8 billion in new tax revenue for the states is nothing to sneeze at. Those funds help support public services that, ironically, are often strained by the very social costs illegal gambling exacerbates.

Even states that legalize sports betting have attached such strenuous taxes, licensing requirements, and limits on competition that the entire enterprise becomes pointless. Montana is one such example, explained in the Consumer Choice Center’s Sports Betting Index ranking of regulation schemes nationwide.

Legalized sports betting isn’t without downsides, which almost every proponent would acknowledge. Its critics, however, take an absolutist position that ignores half the body of evidence, because bans are the purest expression of a personal disdain for gambling.

However, as with all public policies, we must recognize that regulated markets with consumer protections are a far better scenario than attempting to simply ban it and hope sports betting will magically disappear. It won’t, and consumers deserve better.

Stephen Kent is the Media Director for the Consumer Choice Center. Follow him on X @StephenKentX

Post Comment